Content adapted from an article originally published by, and used with permission from, Fiducient Advisors LLC.

Nonprofit organizations may experience several investment paradoxes throughout the portfolio creation process. Our team unpacks four of the most common.

1. A lower spending rate can lead to a greater spend allowance.

A well-designed spending policy is essential for both advancing an organization’s mission and safeguarding the corpus of an endowment. Identifying the right spending model which aligns with the organization’s needs is crucial for long-term success and maintaining intergenerational equity.

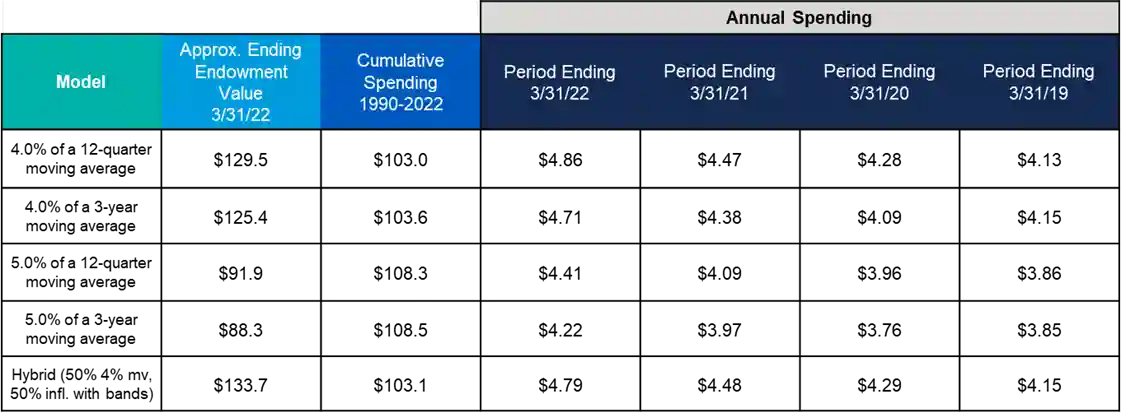

Shown in the chart below, a higher preliminary spending allowance often resulted in a lower annual spending allowance over time. Why? The initial higher spending rate significantly eroded the endowment’s corpus, which means that over time, using a 5% spending allowance resulted in a progressively smaller dollar amount allocated for spending. Conversely, implementing a “lower” spending allowance of 4% would, over time, allow the endowment to have a greater annual spend allowance.

An annual review of an organization’s spending trends is a vital component of fiduciary governance. Spending practices should be regularly assessed to ensure the endowment is in alignment with guiding principles established in the Investment Policy Statement. This should include proactive planning for cash needs and avoiding unnecessary special appropriations. While we understand the challenge of reducing an existing spending rate, the long-term impact of choosing a higher spending rate could significantly reduce the corpus.

Sample portfolio using a starting market value of $50 Million on 1/1/1990.Assumes actual historical market returns, using a generic portfolio of 80% MSCI ACWI Index and 20% Barclays Aggregate Index. CPI is the measure of inflation. The hybrid model uses a 4% spend and bands of 3-6% of endowment value.

2. Market timing trades small profits for big risks.

Market volatility may prompt committee members to take reactive measures in an attempt to “safeguard” the portfolio. Such actions, however, could potentially lead to missed opportunities, lower returns, and harm to long-term nonprofit investors. Although market timing is widely recognized as a risky and often ineffective strategy, there are moments when the need to respond to difficult market conditions may feel unavoidable.

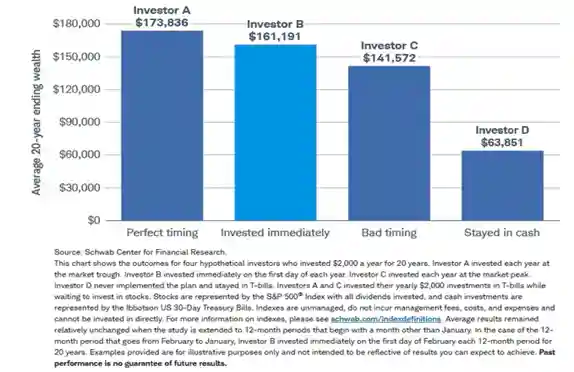

Charles Schwab’s research group explored five different investment strategies using a hypothetical $2,000 invested in the S&P 500 at the start of each year over a 20-year period (2003-2022).1 Each investor adopted a unique approach, from Peter Perfect, who perfectly timed his investments in the market on the best days of each year, to a more conservative investor like Larry Linger, who kept his funds in cash, represented by Treasury bills. The research results were surprising: despite Peter Perfect’s (Investor A) impeccable timing, his portfolio only outperformed Ashley Action (Investor B)—another hypothetical investor who simply invested the $2,000 on the first trading day of each year—by just $10,537 over 20 years.

Charles Schwab extended their research by averaging the results of 78 distinct 20-year periods for four of the five investors, excluding Matthew Monthly, a hypothetical investor who utilized a dollar-cost averaging strategy. The findings, illustrated in the graph below, showed that Peter Perfect’s strategy (represented by Investor A) led to wealth accumulation only marginally higher than that of Ashley Action (represented by Investor B), with a difference of just $12,645. More importantly, timing an investment perfectly is much easier to achieve when looking through the rearview mirror. The reality is that “perfectly” timing the market is nearly impossible. Further analysis revealed that this trend held true across different time periods. Even when considering 78 rolling 20-year periods from 1926 onward, the results remained consistent – timing the investment perfectly would not allow for a significant return. Mistimed investments carry several risks, as shown by Investor C’s strategy, who invested at the market’s peak when sentiment was at its highest — an example we will examine in the third paradox. On the other hand, there are also risks associated with inaction, as demonstrated by Investor D, who missed the opportunity to capitalize on market gains.

Ultimately, for nonprofit committees responsible for long-term investment decisions, the key takeaway is clear: staying the course and enduring market fluctuations is the most effective approach for sustaining and growing investments over time.

3. Market returns may be strongest when investor sentiment is weakest.

A paradox exists in the cyclical nature of financial markets, where returns are often strongest when investor sentiment is weakest. While it is natural for committee members to want to retreat during times of fear and uncertainty, yielding to that sentiment can negatively affect the portfolio. Giving in to fear creates a domino effect — asset prices may fall, but that may lead to reward for those willing to go against the grain. On the other hand, when excitement drives market performance, valuations and prices tend to rise, often making assets more expensive for the optimistic investor. Fear leads to selloffs, while excitement can inflate bubbles. On average, the U.S. stock market tends to peak approximately six months2 before the economy does and tends to trough approximately five months before the end of recessions.3 This inverse relationship shows us that low investor sentiment has greater correlation with the actual economy and less with the market itself. Historically, some of the best returns have come during times of widespread pessimism, with prices rebounding once sentiment improves. Recognizing that optimistic (bull) markets usually last longer than pessimistic (bear) markets can help committees maintain confidence in market outlook and broader trajectory, reducing the urge to alter asset allocations just to “safeguard” portfolios. Economic cycles of expansion and contraction are natural occurrences, and committees should embrace these fluctuations without apprehension.

4. The Dilemma of Extrapolating Data

It’s human nature to seek to eliminate uncertainty. We are taught that history often repeats itself, which leads us to instinctively rationalize events and draw connections between them. Extrapolation, which involves predicting an unknown value based on past events or data, is one way that investors try to reduce uncertainty. Various techniques are used to forecast future trends, which can shape sentiment on market outlook. However, relying on data extrapolation for portfolio decisions without understanding its limitations can be risky, as historical data does not guarantee future returns. Identifying patterns or utilizing trends as a guide does not guarantee future outcomes, as markets can be unpredictable and sometimes irrational. So, how can investment committees navigate the future amid uncertainty? A long-term perspective and a diversified portfolio are essential strategies for nonprofits and endowments. These approaches offer the best protection against market fluctuations and help prevent hasty, reactive decisions.

Committees must recognize the importance of staying invested through all market conditions, even during periods of market volatility. Maintaining discipline, adhering to a structured strategy, and reviewing asset allocations annually can help endowment and foundation investors keep their portfolios prepared for future market events without reacting to the noise.

Wealthspire’s Approach: Our Work with Endowments & Foundations

If you’re considering building an investment committee for your affiliated nonprofit, our advisors can help guide your organization throughout the process. We have the experience and capabilities to establish clarity and key objectives while incorporating an investment strategy that aligns with your organization’s mission and helps address capital preservation needs. Want to learn more? Contact a member of the Wealthspire team to learn how we can work with you.

[1] Source: Examining Four Investment Paradoxes for Nonprofits and Endowments – FIDUCIENT – FIDUCIENTADVISORS.COM

[2] Source: Russell Investments, “Is the U.S. stock market looking through the recession? History has the answers.” August 2020.

[3] Source: Schroders, “How do US stocks and earnings usually perform during recession?” December 2022.

Wealthspire Advisors LLC, Fiducient Advisors LLC, Wealthspire Retirement, LLC dba Wealthspire Retirement Advisory, and certain other affiliates are separately registered investment advisers. © 2025 Wealthspire Advisors

This material should not be construed as a recommendation, offer to sell, or solicitation of an offer to buy a particular security or investment strategy. The information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon for accounting, legal, or tax advice. While the information is deemed reliable, Wealthspire Advisors cannot guarantee its accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose, and makes no warranties with regard to the results to be obtained from its use.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk. Therefore, there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment or investment strategy, including the investments and/or investment strategies recommended and/or undertaken by Wealthspire Advisors, or any non-investment related content, will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated historical performance level(s), or prove successful. No amount of prior experience or success should be construed that a certain level of results or satisfaction will be achieved if Wealthspire Advisors is engaged, or continues to be engaged, to provide investment advisory services.

Historical performance results for investment indices, benchmarks, and/or categories have been provided for general informational/comparison purposes only, and generally do not reflect the deduction of transaction and/or custodial charges, the deduction of an investment management fee, nor the impact of taxes, the incurrence of which would have the effect of decreasing historical performance results.